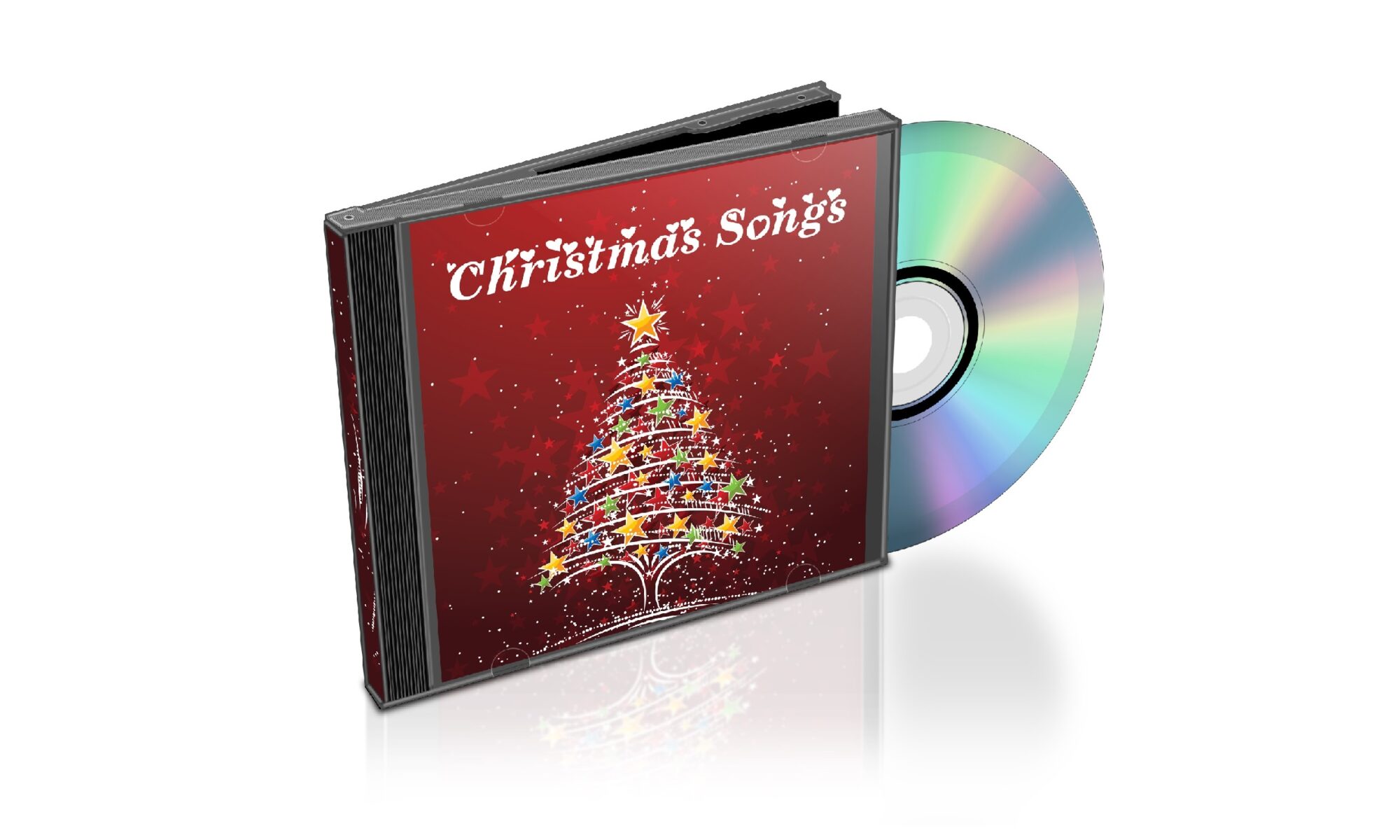

With the holidays fast approaching, we are once again exposed to familiar songs that warm our Christmas-loving hearts. Nowadays, it is not uncommon to catch Mariah’s All I Want for Christmas is you, Britney’s My Only Wish (This Year), and Jose Mari Chan’s Christmas in our Hearts (and uhm, a bunch of his other songs), playing in our favourite malls, stores and restaurants.

To many customers, listening to Christmas songs is a pleasant experience. And if you happen to own a store, it is tempting to play these songs in order to attract visitors. After all, studies show that listening to certain songs could affect purchasing behaviour.[1] However, how do you know if a song could be played to the public, free-of-charge?

I. Applicable Laws

Songs are covered by copyright. Our law treats musical compositions as original intellectual creations that are protected from the moment of creation.[2] For instance, song composers hold exclusive rights to public performances of their works.[3] Performers, producers of sound recordings and broadcast organizations also hold other exclusive rights over the publication of their respective works.[4] As a consequence, an establishment may have to secure licenses and pay royalties in the form of license fees in order to play copyrighted songs in public.[5] Failure to do so may result in a finding of infringement, which entails imprisonment for one to three years and payment of a fine ranging from P50,000 to P150,000 for the first offense alone.[6]

II. Exceptions

It must be noted, however, that the Intellectual Property Code lists down a number of limitations to this rule. Some acts are not considered as infringement. An example is where the recitation or performance is made strictly for a charitable institution and involves a work that has previously been lawfully made accessible to the public.[7] There is also no infringement where the use of copyrighted works amounts to fair use, as when a song is played in public for purposes like research, criticism and teaching.[8] Notably, a recent case decided by the Court of Appeals went further and held that certain food service and drinking establishments that have limited areas, seating capacities and speakers, are exempted from paying license fees.[9] It remains to be seen, however, whether the Supreme Court will adopt this ruling.

III. Public Domain

Most importantly, not all songs are subject to copyright. In a case, the Supreme Court held that although playing the combo in a restaurant for the purpose of entertaining and amusing customers are acts constitutive of performance for profit as contemplated by our Copyright Law, there can be no infringement if the songs played form part of the public domain.[10] Songs, whose copyright protection have already expired, move to the public domain and may henceforth be played and performed in public without liability.[11] Examples of these are Christmas classics like Jingle Bells, We Wish You a Merry Christmas and Silent Night.[12] In the Philippines, copyright protection over a work generally extends until 50 years after the author’s death.[13]

In summary, if you wish to impart the Christmas vibe to your customers, it would be wise to apply for the necessary licenses or to simply choose songs that are available in the public domain. Better yet, why not create your own Christmas jingles?

For questions regarding this article, please email us at inquiry@cfiplaw.com.

Note: The article above is for informational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice.

[1] https://www.psychologistworld.com/behavior/ambient-music-retail-psychological-arousal-customers.

[2] Sec. 172.1 (f) IP Code (1997).

[3] Sec. 177.6 IP Code (1997).

[4] Secs. 203, 208, 211 IP Code (1997).

[5] https://filscap.org/frequently-asked-questions/.

[6] Secs. 217.1 (a) IP Code (1997).

[7] Sec. 184.1 IP Code (1997).

[8] Sec. 185.1 IP Code (1997).

[9] https://www.manilastandard.net/lgu/luzon/237697/ca-upholds-ruling-vs-filscap.html.

[10] Filipino Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers, Inc. vs Benjamin Tan, G.R. No. L-36402.

[11] https://www.ipophil.gov.ph/news/how-to-perform-and-play-songs-in-public-the-legal-way/.

[12] https://library.osu.edu/site/copyright/2018/12/21/public-domain-christmas-songs/.

[13] Sec. 213.1 IP Code (1997).